SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

| Lake Powell, one of the two largest reservoirs in the Colorado River system along with Lake Mead, is at historically low levels. Photo: U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Flickr Creative Commons. Click to enlarge. |

Issue Backgrounder: Can States Divvy Up the Shrinking Colorado River Water Supply?

By Joseph A. Davis

“Whiskey is for drinking; water is for fighting over,” according to Western oral tradition. That reflects how water law in the arid West is quite different from water law in eastern states.

The basic premise is that water out West is very finite, and in fact scarce. That has meant people have to sue to get theirs, and thus was spawned a legal pecking order of seniority in water rights.

It has also meant the building of huge federal water projects to somehow undo the dryness.

Tying together the water-related environmental problems of a big part of the American West is the Colorado River.

And now its problems are growing so large they will not stay out of the news. One immediate issue is a troubled “drought deal” — which was supposed to be all done Jan. 31. But it wasn’t.

|

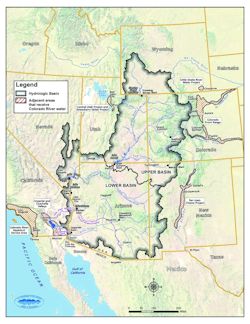

| A map showing the seven Colorado River Basin states. Image: U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Click to enlarge. |

The “drought deal” of headlines is more properly the “Drought Contingency Plan.” The entire Colorado basin system has been beset by a long-term drought since about the year 2000. Yes, climate change has a lot to do with it, but the problem goes much deeper.

Regardless of the causes, the current issue is what to do about it. The story involves at least seven states, the federal government, some Native American tribes, a hornet’s nest of irrigation districts and even Mexico.

Colorado River Compact at core of conflict

The Colorado River and its tributaries drain 246,000 square miles, portions of seven states: Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada and California.

Over the past century, a series of dams has stored its waters, making it useful for irrigated agriculture, hydroelectric power and urban drinking water supply.

They include Granby Dam and the Grand Valley Diversion Dam, both in Colorado, the Glen Canyon Dam in Arizona, the Hoover Dam in Arizona and Nevada, the Parker Dam in Arizona and California, and the Imperial Dam in Arizona and California. The Glen Canyon Dam forms Lake Powell and the Hoover Dam forms Lake Mead — the two largest reservoirs in the system.

Together, all the dams can store more than 58 million acre-feet of water. But right now they don’t. And that’s the problem.

The regulation of Colorado River water flow and use is institutionally very complex — but the Colorado River Compact and the “Law of the River” are at its core.

The compact was agreed upon in 1922 by the seven basin states and the federal Bureau of Reclamation. One key provision divides states into the Upper Basin (Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming) and the Lower Basin (Nevada, Arizona and California) — and importantly allocates the same amount of water (7.5 million acre-feet) to each of them over a ten-year averaging period.

That may have looked good in 1922. The problem, today, is that there is not that much water in the river. The water allocations in the 1922 compact were based on an abnormally wet period.

The cascading tree of water rights built on

the foundation of the Colorado River Compact

is extensive — but it amounts to more

rights (“paper water”) than “wet water.”

They call it “overallocation” or “structural deficit.” The cascading tree of water rights built on the foundation of the compact is extensive — but it amounts to more rights (“paper water”) than “wet water,” as shown in this graphic.

Looked at through one lens, a lot of the river’s water comes from snowpack in the mountainous upper basin, where demand is lower; a big part of the demand comes from the arid lower basin, where cities and farms were created in the desert.

The Southwest is arid to start with. Then there are natural drought cycles that make that aridity even worse. That means overuse of available water is drawing down the reservoirs.

Development of farms and cities is raising the thirst for water in downstream areas. And on top of all that comes the long-term trend of global climate change. It may reduce precipitation and snowpack, increase evaporation via higher temperatures and bring an irreversible longer-term drying trend.

Drought contingency plan remains unfinished

In December 2017, the Bureau of Reclamation called on the seven compact states to come up with a set of “drought contingency plans.” Each state, as well as each basin, had to develop one.

Collectively, the plans were to function as an agreement, a set of commitments to conserve water and voluntarily refrain from demanding all the water parties may be legally entitled to. A great deal of negotiation followed.

The drought contingency plan may,

in the end, be just a bandaid,

offering at best a few years’ relief.

It seemed like big news when water managers announced in Oct. 2018 that they had concluded a draft agreement. The problem was that each of the state governments and relevant agencies had to ratify what the negotiators had agreed on.

Many states, particularly in the upper basin, did just that. The Bureau of Reclamation finally set a deadline of Jan. 31, 2019, for states to ratify, with Arizona seeming to be the only holdout.

The Arizona legislature burned the midnight oil and seemed to make it just under the wire before the deadline. But when the smoke had cleared, glitches in the agreement remained.

Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Brenda Burman announced in a press call the next day that “close is not done.” She called on governors to submit ideas on how to fix the problem and set a new deadline of March 4.

The issues came from downstream states.

In Arizona, for instance, misgivings were voiced by the Gila River Indian Community, for whom the state did not speak. A few days later, those problems had been smoothed over.

In California, the Imperial Irrigation District, with priority Colorado water rights, demanded some $200 million in federal cash to fix drought-induced problems in the Salton Sea. Extra assurances from the Bureau of Reclamation seemed to allay that problem.

But the March 4 deadline came and went, and the Bureau of Reclamation still did not think a deal had been done — and was still threatening to write the plan itself.

The problem, in essence, was that a constellation of water users (like irrigation districts and utilities) in California and Arizona were still not clearly on board. Bureau of Reclamation says all those lower level entities need to sign agreements, too.

Complications include politics, international sharing, agriculture

Whether the drought deal will ever be sealed to the satisfaction of Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Burman remains an unknown.

But if the administration does follow through on its threat to impose a drought plan on the states and water users, that could end up hurting President Donald Trump. Nobody wants their water, or water rights, taken. And the timing could collide with the 2020 election. Stay tuned.

Just to make things more difficult, remember that the Colorado River goes through Mexico before it ends in the sea. The United States and Mexico recently concluded an agreement on Colorado River management. That will not hold up the drought contingency plan.

|

| Officials with International Boundary and Water Commission, United States and Mexico, after signing of a new binational water scarcity plan for the Colorado River basin in September 2017. Photo: U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Flickr Creative Commons. Click to enlarge. |

Getting a real drought deal for the Colorado River is important. The Colorado irrigates some four million acres of agricultural land, helping grow a significant share of the nation’s food and feed. It provides drinking water to an estimated 40 million people.

But the Lake Mead and Lake Powell reservoirs are historically low — so low that engineers worry they may reach the “dead pool” stage where they can no longer generate power.

The deal may, in the end, be just a bandaid, offering at best a few years’ relief. If water use, along with water rights, continues to exceed the flow of the river, reservoirs may keep dwindling.

Big cities like Los Angeles, Tucson and Phoenix will grow in the dry lands, as will their thirst. Water projects like the Central Arizona Project, funded with generous federal help years ago, will keep demand alive. And climate change, which has already started — and started further drying the Southwest — will inevitably make the problem worse.

More reading

Western water has inspired a whole lot of great journalism, partly because of these conflicts.

You might read books like “Cadillac Desert” by Marc Reisner, “A River No More” by Philip L. Fradkin, “Water Is for Fighting Over” by John Fleck, “Where the Water Goes” by David Owen and more.

Among the living masters are Fleck (see his blog), Ian James at the Arizona Republic, Matt Weiser at Water Deeply (which recently “paused” publication) and Abrahm Lustgarten for his series for ProPublica, "Killing the Colorado."

Joseph A. Davis is a freelance writer/editor in Washington, D.C. who has been writing about the environment since 1976. He writes SEJournal Online's Issue Backgrounders and TipSheet columns, directs SEJ's WatchDog Project and writes WatchDog Tipsheet and also compiles SEJ's daily news headlines, EJToday.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 4, No. 11. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement