SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

Feature

By ROBERT McCLURE

As key statute hits 40, how to tell the story of its successes, failures

|

|

|

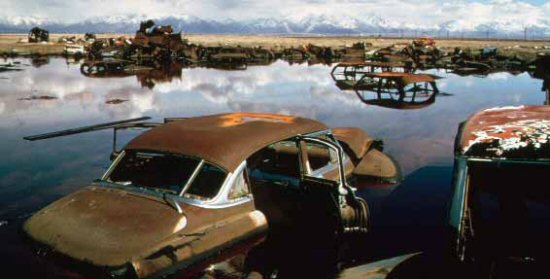

In 1974, a photographer with the EPA’s Project DOCUMERICA discovered these decaying auto hulks in an acid and oil-filled pond within sight of Utah's majestic Wasatch mountain range. It was later cleaned up under provisions of the newly passed Clean Water Act to prevent contamination of a wildlife refuge and the Great Salt Lake nearby. PHOTO BY BRUCE MCALLISTER, EPA-DOCUMERICA/ NARA. |

The Clean Water Act, a bedrock environmental law passed four decades ago in the wake of Silent Spring and the first Earth Day, is showing its age. Not only has it failed to deal with the pollution it set out to end, it also hasn’t kept pace with the growth of our cities, new trends in agriculture and the explosion in the number of new chemicals unleashed on the landscape.

With the statute’s 40th anniversary coming up in October, there is a revelatory story to be done about how the Clean Water Act affects your readers, listeners or viewers, no matter what geographical scale you report on, from hyperlocal to national.

Let’s take a look at how to turn what could be an exercise in ho-hum anniversary journalism into a serious critique of value and relevance to your audience.

Law’s successes marred by ongoing violations

It’s first helpful to know what the drafters of the Act intended. It’s startling to go back into the history of the law and see that the framers of this law decreed:

“It is the national goal that the discharge of pollutants into the navigable waters be eliminated by 1985 …

“It is the national policy that the discharge of toxic pollutants in toxic amounts be prohibited …

“It is the national policy that programs for the control of nonpoint sources of pollution be developed and implemented in an expeditious manner …”

Yes, that’s right — when the law passed in 1972 it was supposed to end water pollution within 13 years. Ambitious as that may sound today, it’s a powerful point of comparison when you consider how much hasn’t happened to achieve that goal, even after 40 years. Those goals represented what the public was calling for in 1972, and what the public apparently still expects today: that water pollution be illegal and not be allowed.

Yet something like one-third of the nation’s lakes, bays, rivers, streams and sounds remain in violation of the Clean Water Act.

|

|

|

Thick, acrid smoke poured up from a fire on the surface of Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River in November, 1952, one of more than a dozen such incidents on the industrial waterway dating back almost a century. A similar blaze in 1969 was instrumental in the 1972 passage of the Clean Water Act that led to the river’s eventual recovery. PHOTO: CLEVELAND PRESS COLLECTION, CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY. |

Any fair discussion of the Clean Water Act must acknowledge the massive amount of progress the law has spurred. Recall that passage of the law over President Richard Nixon’s veto in 1972 was spurred in part by a Time magazine story on the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland actually catching fire because so many combustible wastes had been dumped into it. (That 1969 blaze in Cleveland was not the first river fire, nor the last, just the most famous one. The Cuyahoga had previously caught fire, as had those in other cities.)

The Clean Water Act has done a pretty good job of getting polluters to reduce the amount of gunk being dumped, particularly if it’s getting dumped through a pipe. (That makes it a so-called “point source,” meaning the pollution discharge is coming from a particular point, the discharge pipe.) The law has done a much worse job controlling “non-point” pollution that flows off hard surfaces including streets and parking lots, as well as from farm fields and construction sites and other types of land uses.

Understanding the Act’s inner workings

|

|

|

The contemporary Cleveland, Ohio skyline beyond the Cuyahoga River in 2009. PHOTO: |

Some of the basic building blocks of Clean Water Act enforcement will help you assess the health of a particular water body, and the efficacy of government enforcement efforts.

Here’s how enforcement of the Act is supposed to work:

First a state or tribe decides what the “designated use” of a given water body will be. In practical terms, this is not usually a big deal. Most of the water bodies are supposed to be fishable and swimmable, and some also are supposed to support other uses such as drinking water, livestock watering or irrigation.

Then the government — usually states, but in some states the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency — establishes water quality standards and goals. If any particular water body is meeting these standards, regulators are supposed to apply a multitiered “antidegradation policy.”

Theoretically, combined with monitoring, this is designed to prevent deterioration of water quality in healthy water bodies to the point that existing uses are preserved. That doesn’t always happen, though. You’re likely to hear a lot about this if, say, a new factory or sewage treatment plant wants to dump waste into a water body that’s just barely able to support the uses for which it is designated. Certain pristine “outstanding national resource waters” receive the highest protection — no permanent reduction in water quality is allowed.

More interesting is what happens if a lake, stream or river does not meet water quality standards.

At that point, the water body is placed onto what’s known as the 303(d) list — named for a section of the Clean Water Act — meaning that it is in violation of the Act. The 303(d) list is a great starting point for any state, regional or local stories. In the latest count, the number of “impaired” water bodies ranged from 35 in Alaska to 6,957 in Pennsylvania. From this list you can determine which water bodies are violating the Clean Water Act, and what types of pollutants are involved.

The untold stories of monitoring, cleanup

Some years ago the 303(d) list was merged with something known as the 305(b) list, which attempts to assess the health of all water bodies and recommend actions needed to achieve water quality standards.

The merged lists are now presented as what’s known as an Integrated Report, which is due to EPA on April 1 of every even-numbered year. It’s worthwhile to take a look at these, and compare them to past versions.

Pay close attention to the 305(b) list. It will tell you, for example, what percentage of your state’s water bodies are even monitored — a quick and dirty story in and of itself, since it’s likely to be surprisingly low.

More important, this list is the universe from which the agency chose those waterways that went on the 303(d) list. Did your budget-battered state environmental agency put fewer waterways on the list than it should have? Remember that the more water bodies on the list, the more work the agency has to do. Ask probing questions about how the state made decisions to leave water bodies off the 303(d) list.

|

|

|

Wading through knee-deep waters, a young participant in the 2011 Los Angeles River Day of Service in California picks up accumulated trash. PHOTO: |

When a water body is on the list of impaired waters, often a cleanup plan known as a Total Maximum Daily Load, or TMDL, will be drawn up. EPA and the states have been forced by several rounds of lawsuits to produce these plans. They attempt to sort out the sources of a given pollutant, and lay out ways to reduce the pollution sources to a point where the water body again complies with the Clean Water Act (for that pollutant, at least).

Now, here’s the dirty secret that doesn’t get nearly enough attention: The Clean Water Act requires these TMDL cleanup plans to be drawn up, but it doesn’t require them to be put into effect.

So there is a fine story to be done in almost any city or state about how officials know how to bring water bodies into compliance with the Clean Water Act, but aren’t taking action.

Permits, extensions yield important stories

One of the most accessible ways to cover the Clean Water Act at the local level is to take a look at one or more of the sewage treatment plants, feedlots, factories and other facilities regulated under the law.

A major pollution-control strategy of the Clean Water Act is requiring facilities that discharge waste into waterways to obtain a permit to do so, usually from a state pollution-control agency. These are known as National Pollution Discharge Elimination System permits, known by the acronym NPDES (pronounced NIP-deez).

How those permits are drawn up is a key matter.

The original idea behind the permits was that regulators would require what could reasonably be achieved in terms of pollution reduction from factories, sewage plants and other dischargers. The facilities would be held to limits in those permits, which were to be issued for a period of five years. Theoretically, in the intervening five years technology would improve and when the next permit was issued, the polluters could be held to a higher standard. The pollution limits would be gradually “ratcheted down” to zero.

That was the theory, anyway. It often hasn’t worked out that way. It’s worth looking at the largest dischargers in your area and examining their permits. Are the limits being ratcheted down over the years? Some expert guidance from a university or knowledgeable environmental advocate will be helpful here.

For a given facility, look at current and past permits. Ask, have the discharge limits been reduced? How often is the discharge tested? What about the waterway into which the gunk is dumped? (You’d be surprised how little actual measurement is done there.) How were the pollutants being monitored (often known as “parameters” or “parameters of concern”) selected in the first place?

Don’t overlook a huge trend, which is how overwhelmed are the state agencies issuing administrative extensions of these permits? If you see permits being extended for long periods, remember that it’s more than an administrative detail. The permit renewals are intended to re-examine the pollution-control strategy, and they give the public a formal say in how those limits should be set. But if a five-year permit gets extended for four years, that’s four years’ worth of pollution — without public comment.

In general, these NPDES-permitted facilities will be required to monitor what they are dumping and report to the state environmental agency. These “discharge monitoring reports,” or DMRs, typically are submitted on a monthly basis, although some are done quarterly. Some larger facilities sample more frequently, even though they only have to submit their reports monthly.

Mapping compliance can show surprising problems

For an even broader look at how the Clean Water Act is functioning, consider taking a virtual look across the landscape.

Typically a state environmental agency will have a large database that includes the discharge reports. Once you obtain this, you will see that many facilities are violating the Clean Water Act, some continuously or at least frequently. Laying those out on a map is impressive. Even better, make it an interactive map so that members of the public can learn the details of what’s going on at the polluters nearest them.

EPA has its own permit compliance database. But the ones at state agencies will be more up to date, in my experience. [In February of this year EPA unveiled a new and supposedly easier-to-use tool, the DMR Pollutant Loading Tool, although as I write this shortly after its release, I haven’t personally used it yet].

When we did this mapping at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, complete with color-coding, readers couldn’t believe the amount of facilities that were violating the law.

Some years later, The New York Times went further on a national basis with its 2010 Toxic Waters series, calculating the number of enforcement actions per 100 violations of the Clean Water Act.

The results were surprising. In my home state of Washington, for example, just 8 percent of violations resulted in enforcement. Perhaps surprisingly, North Carolina led the nation, with 85 percent of violations sparking enforcement (although the Times pointed out that resulting fines were relatively small, averaging just $1,387 per violation.)

In addition to spotting those facilities that are violating their permits, consider looking at the scandal in what’s legal.

For example, say Facility A is allowed to have a concentration of toxic metal No. 1 of 200 parts per million in its discharge water (a/k/a “effluent”). Take a look at the actual number of gallons that were discharged over, say, a year. If that facility discharged 500 million gallons in a year — not that large a number for a big sewage treatment plant — that means 5,000 gallons of the toxic metal were discharged.

If you carry out that exercise with even the largest, say, 10 or 20 dischargers into a water body, the numbers begin to add up very fast.

Truly, the Clean Water Act is so far-reaching that we could fill up this entire issue of the SEJournal with more story ideas, but you’ve got the basics now. See the the following section of this story for a few other ideas for how you can shed light on how this bedrock environmental statute is functioning four decades after Americans thought their waterways were to be protected.

Other clean water story ideas

• States and tribes must update their water quality standards every three years. What’s happening in your part of the world?

• As mentioned in the above, the Clean Water Act has done a poor job overall in controlling so-called “non-point source” pollution washed into waterways as rainwater runoff a/k/a stormwater a/k/a non-point source pollution. The remedies involved so-called “green infrastructure” that environmentalists say should be part of all new construction and rebuilding projects. SEJournal and SEJ’s TipSheet have covered this extensively in the past.

• Consider that EPA’s original list of 129 contaminants to be controlled, issued in 1977, has never been updated, even though thousands of chemicals have come into use since then. Personal-care products such as shampoos and medicines are moving over and through our bodies and into the waterways. In some places, such as Seattle, scientists have noted female traits in male fish, theorizing that synthetic estrogens are at work. A broad category frequently implicated is phthalates, which are used in a wide variety of consumer products. But there are many other chemicals in many other products that have an estrogenic effect.

You will find more here and here.

• A hardy perennial of environmental coverage in many locales is the so-called “concentrated animal feeding operations,” or CAFOs. If you have these in your coverage area you probably have heard about them. The 40th anniversary of the Clean Water Act is a great time to look carefully at this source of water (and air) pollution.

Robert McClure is executive director of InvestigateWest, a non-profit journalism studio based in Seattle and covering the Pacific Northwest. He also serves on the SEJ board of directors and is chairman of the SEJournal editorial board.

SIDEBAR

Online Resources for Covering the Act:

|

- One place to start is EPA’s main web page on the Clean Water Act with a good overview of the law.

- Text of the Clean Water Act.

- Even as a veteran of Clean Water Act coverage, I found it helpful to take this “fact or fiction” quiz that lays out some basics and will give you some good questions to pursue.

- Here is a barrelful of information on Total Maximum Daily Loads.

- This site looks at TMDL lawsuits, by state.

- Excellent SEJ TipSheet on the new Discharge Monitoring Report Pollutant Loading Tool.

- Here’s a good Clean Water Act glossary.

* From the quarterly newsletter SEJournal, Spring 2012. Each new issue of SEJournal is available to members and subscribers only; find subscription information here or learn how to join SEJ. Past issues are archived for the public here.

CHRIS CAPELL VIA FLICKR.

CHRIS CAPELL VIA FLICKR.

Advertisement

Advertisement