SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

Special Energy Report: Part Four

By JENNIFER WEEKS

|

|

|

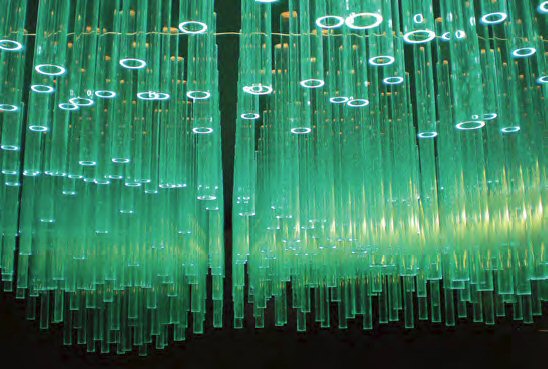

Once destined to contribute to the country’s solar power development, almost 1,600 specially designed glass tubes instead ended up as part of a public art exhibit named Sol Grotto 4 at the UC Berkeley Botanical Garden, after they were abandoned at a San Jose, Calif., warehouse following the bankruptcy of Solyndra. In like manner, energy stories can take unexpected, circuitous and possibly even fortuitous twists and turns. Photo: |

More than one observer has compared covering energy to the folk tale about the blind men who try to describe an elephant, and end up shouting at each other because they’ve each grasped a different part of the beast and believe their portion represents the whole thing.

Writing last year in Grist, David Roberts neatly summarized the challenge:

“[T]here is no singular ‘energy journalism,’ only various tribes with various beats... There are finance and business journalists who cover energy as a commodity business, tracking global supply and demand flows, prices, futures trading, all that sort of stuff. There are business and tech journalists who focus on clean tech. There are environmental journalists, who tend to cover energy (when they do it) through the lens of enviros vs. polluters. And there are political journalists who cover energy as a campaign and/or policy issue, sometimes as a specialty, more often as part of a portfolio.”

If the many angles of energy reporting are a challenge, then stories that address more than one dimension are likely to be better than articles that describe only one. As an example, consider ProPublica’s award-winning coverage of the natural gas fracking boom. This expansive series (147 stories as of mid-March) includes many detailed accounts of harmful impacts to land, water and air from fracking operations, but it has also looked closely at the issue from other angles, including the adequacy of federal and state oversight, impacts on Native Americans, and pushback from local communities.

Most journalists don’t have anywhere near that kind of scope, but it’s possible to consider energy from several angles even in a single article. In a March 7 story for The Guardian (“Energy Poverty Deprives 1 Billion of Adequate Healthcare, Says Report,” flagged by Andrew Revkin’s Dot Earth blog), Claire Prevost summarized a report from the NGO Practical Action on “energy poverty” — the social impacts of living without access to reliable energy supplies in low-income countries. It’s not news that energy networks are patchy and unreliable in India, Kenya and many other developing nations. But this story focused on human impacts of those shortages, such as clinics that can’t offer vaccines because they have no refrigerators to store them, and children who try to learn in dark classrooms during blackouts.

Examples like these show how central energy is to modern life, and why energy demand is growing sharply in the developing world.

Avoid the ‘gee whiz’ and the lazy

The flip side is true — if multidimensional stories make good energy journalism, then one-dimensional stories make bad energy journalism. One archetype to avoid is the gee-whiz technology story, which breathlessly predicts that some new concept — an exotic biofuel, a Generation-X reactor design — will be a revolutionary breakthrough, without any discussion of cost, risk, regulatory hurdles, or other speed bumps that the technology may face.

Similarly, lazy reporting on energy politics boils complex public choices down to dueling slogans (“Drill, baby, drill”/“All of the above”), but lets officials maintain contradictory positions like praising free markets while voting for ethanol subsidies.

Knowing some history of U.S. energy policy, and of technologies that have been tried before, can offer valuable perspective on current debates. For example, in assessing expansive projections of recoverable energy from shale oil, it’s useful to know (as Margaret Kriz Hobson wrote in 2012) that oil shale production has cycled through booms and busts in the United States for more than a century, but the technology has yet to be proven.

And no journalist should write about the idea of achieving energy independence without watching Jon Stewart’s “Daily Show” review of pledges from presidents Nixon through Obama to reach that goal.

Advice on improving your energy reporting

Here, from an unscientific survey of a half-dozen energy experts with experience in state government, utility regulation and environmental NGOs, are some additional suggestions for improving energy coverage:

- Challenge dogma and assumptions by all sides — policy makers, environmentalists and businesses. Be skeptical of assertions that any single source — coal, wind, conservation — can meet all or most of our needs.

- Corollary: Do the math. It doesn't require calculus to test ideas like former Vice President Al Gore's 2008 proposal to generate 100 percent of U.S. electricity from zero-carbon sources within a decade. Start with reference sources like the U.S. Energy Information Administration and the International Energy Agency, but be aware that even respected agencies can get forecasts wrong.

- Avoid false choices — for example, energy supply vs. environmental protection, or conservation vs. production. ("At this point, these are just excuses not to think," one source commented.)

- Understand the scale of technological change that is occurring in the power industry — notably, the impact of information technology — and explore how it will affect consumers.

- Recognize that 51 state-level jurisdictions (plus electric cooperatives and municipal agencies and federal agencies) control the pace of decision making about electric power generation, transmission and distribution, with all of the experimentation and chaos that this situation implies.

- Understand how utilities consider the environment in their planning processes, and how they manage risks — for example, fluctuating fuel prices or potential new environmental regulations — as they consider long-term investments.

- Recognize how easy it is for government to do nothing and how hard it is to do something, especially in a political climate in which well-funded people are hostile towards government.

- Pay more attention to energy issues in other countries, such as China's long-term planning and its pledge to impose a carbon tax by 2015.

Jennifer Weeks is a freelance writer and SEJ board member who has covered many aspects of energy since 2004, including production, transmission, facility siting, and environmental impacts.

Back to the Special Energy Report main page.

* From the quarterly newsletter SEJournal, Spring 2013. Each new issue of SEJournal is available to members and subscribers only; find subscription information here or learn how to join SEJ. Past issues are archived for the public here.

Ron Sullivan

Ron Sullivan

Advertisement

Advertisement