SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

Between the Lines: From News to Nest, Veteran Reporter Follows Seabirds' 'Improbable Quest'

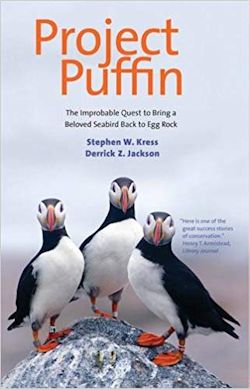

Former Boston Globe columnist Derrick Jackson is a 2001 Pulitzer Prize finalist for commentary who also is an accomplished photographer, having been a semi-finalist in Nature’s Best Photography Windland Smith Rice awards and a two-time finalist in Outdoor magazine’s The American Landscape Contest. He combined those skills for his 2015 book, “Project Puffin: The Improbable Quest to Bring a Beloved Seabird Back to Egg Rock” (Yale University Press). Jackson spoke with longtime SEJ member and freelancer/author Christine Heinrichs about the book for our latest “Between The Lines” author Q&A.

SEJournal: How did you get into journalism?

Derrick Jackson: In high school, I wrote a couple of columns that were book review pieces of “The Autobiography of Malcolm X.” The newspaper printed them, and then I got called to the vice principal’s office. He told me, “Your columns are causing lots of trouble here at school.” He went on, red in the face, for 20 minutes. I guess I listened just enough to what my teachers taught about civics to be able to respond, “Can I ask a question? Do you believe in freedom of speech?” He answered, “Yes, I do. Just leave, and don’t write any of those columns anymore.” I felt like Superman. I had all this power come within me. I just rolled the vice principal with my right to speak! I understood how powerful the pen was. After that, in college at the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, I wrote for the then Milwaukee Journal and the African American weekly, the Milwaukee Courier. I got hired by the Milwaukee Journal after I graduated and covered sports for them for four years.

SEJournal: How did you get from sports to environmental coverage?

|

| The author and his bird of choice. Click to enlarge. |

Jackson: I realized very quickly that there are more things than whether the Knicks beat the Celtics. I loved sports when I was doing it. I often saw the social issues within sports. I realized that who won and who lost games began to interest me less than the implications of sports for society. We always had a joke, that when you can combine sports and politics, the mail truck backs up to the newspaper.

I joined Newsday in 1984 as part of its New York City bureau at a super interesting time. Bernhard Goetz — who became known as the Subway Vigilante — shot four black men on a subway, claiming he was threatened and shot in self-defense, and the police murder of Eleanor Bumpers, an elderly mentally challenged woman [during an attempt to evict her]. I covered big parts of both of those cases and other stuff. The last major thing in news I covered was the Michael Dukakis campaign in 1988, until he won the nomination. My wife was finishing a medical fellowship. We decided that we wanted to live in New England, and I would write for my local newspaper.

My mentor at Newsday was Les Payne, who died this March of a sudden heart attack. He was the national editor, foreign editor, won the Pulitzer Prize as a reporter and directed South Africa coverage. He edited several Pulitzer Prizes and was New York’s most bold columnist. It was a great place, a writer’s paper. They let you stretch your style out, as long as you had your reporting down. Whatever I may possess as a writer, I give credit to Newsday.

My first environmentally-oriented reporting started at Newsday — my two favorite pieces. For one, I went out with bear researchers in Maine, close to where the Appalachian Trail ends. The researchers found females who had given birth, to weigh the cubs and the mothers. It was fascinating to watch them work. They gave one mother a tranquilizer with a long pole and a needle. Then they said, “Move her a little and see if she is out yet.” It was like an earthquake! “Nope, she’s not out yet.” They gave her another, and she was out. Somewhere I have a picture of me with three cubs. I was wearing a red L.L. Bean sweater. They instantly tore it to shreds.

The other story was one in 1986 about this crazy guy, Stephen Kress, who had restored puffins to an island, Egg Rock in Maine. His success was only five years old. The project was still young and fragile. Fewer than 20 pairs of puffins were established on the island. It’s so different when you see one for real up close. It’s a feel-good story.

SEJournal: What was it like working at the Boston Globe?

Jackson: I went to the Boston Globe as a columnist, writing on social issues and occasional sports and society issues. Over the last 10 years, I got interested in public health issues, like obesity. I got interested in the health of the Charles River. I made a hobby of wildlife photography, of the loons, herons and bald eagles. It was all coming together when I joined the Globe’s editorial board.

I got really interested in energy, especially offshore wind. I was covering an industry at its creation in the U.S. I went to Europe, to Denmark and England, and wrote a long piece in The American Prospect about how it’s about to hit the U.S. and how exciting that is.

There are a lot of important things

about racism and sports,

but they don’t matter

if we don’t have a planet.

My youngest son puts it this way, that there are a lot of important things about racism and sports, but they don’t matter if we don’t have a planet.

Offshore wind is the ultimate future. The farther out to sea you can go, the stronger, the more sustained the wind is. On the East Coast, it’s so shallow that it will be traditional stuff, up to a point, to establish the industry. Scotland just started their first floating demonstration farm. Within the last several months, five to 11 floating turbines have been constructed.

It’s really exciting. Having been to Europe, I’ve seen towns that were down on their luck as recent as 10 years ago, after they lost the fishing industry, or the millwork that was their economy. Offshore wind has really helped those towns recover.

SEJournal: How did “Project Puffin” come about?

Jackson: I called Kress up in 2005 and re-introduced myself: I was this black reporter from Newsday back in 1986. He said, “Of course I remember you, you did a good job.” I told him I’d like to come out again for an update. Although it was fun to go out, the interns I encountered there stole the show. The interns that take care of the puffins are a mixture of undergraduates, graduate students working on advanced degrees and an occasional volunteer.

My youngest son was in the Scouts at that time. I’d spent 10 years teaching at Simmons College, an all-women school. So I had a heightened antenna for where the next generation was headed. They are stewards of all things in the environment. You can hear the enthusiasm, and see the care these young adults are willing to take.

|

| Click to enlarge. |

The first column I did was about the interns as much as the puffins. I made it a semi-annual update on the puffins, until they cracked the 100-pair barrier. I wrote about the puffins and two other birds, loons and bald eagles. There are now bald eagles in every state but Hawaii. Eagles were just getting re-established in states other than Maine, in New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Vermont. It was fun to do updates on them all.

The level of conservation necessary is the number one thing Steve Kress learned: There is no such thing as balance. We grew up with the buzz phrase “balance of nature,” but in reality there is no such thing, especially in habitats that have tremendous human interface. In the case of puffins, there will always have to be interns on the islands. We have created an over-abundance of predators, the black-backed gulls and herring gulls. Dumpsters in the back of restaurants, debris from fishing boats and landfills are artificially stimulating the population of gulls. They are absolutely voracious. They will grab a chick, of any species. They eat them like popcorn.

Some success stories have led to conflicts with puffins. The bald eagles are incredible. They are so smart. When the interns are on the island in the summer, the eagles almost never land. In August, when the interns break up the bird lines and take down their tents, close up any housing they have, literally the next day, the day after they left, five bald eagles were hopping around Easter Egg rock looking for late-blooming chicks.

Sea birds present different problems from land birds. For land birds, if you can get rid of DDT and create enough space around nesting areas, they can recover. As long as they have habitat and food to eat, they will do all right. There are peregrines over Boston now. Steve borrowed from ideas that have helped land birds recover, like egg and chick transports. Until he did his, no one had ever restored a seabird to an island where it had been eliminated. We’re still learning, about the limits, the fracturing of habitat, the chemicals we are putting out there.

SEJournal: Tell us about how this became a book project.

Jackson: Steve was friends with a Boston-New York book agent, who had a house near the Puffin Project in Maine. She was a good friend of a former editor on the Globe’s editorial page. She asked my former editor about getting Steve to write the story about putting the puffins back on Egg Rock. “He’s always too busy,” she said. “Do you have anyone who can help him tell the story?” He said, “I have the perfect guy. He’s been writing about puffins for years. Let’s give it a try.”

We did the reporting. My role was to go back and do general history on birds and seabirds as it relates to puffins, such as the Great Auk. Puffins were common along the islands in Maine until farmers and residents exterminated them for meat and eggs, on all except one island. Steve decided to bring them back. My role was to interview key participants in the early days of the project. Steve put in things I couldn’t have known about. It’s written in the first person, as if I were him. I channeled my inner Steve. I had been visiting him for years. It was fun to do, then add some style to it. Yale University Press published the hardcover in 2015. It took a year of reporting. Then a year of writing, then a year of Yale editing it. The book was finally done in fall of 2014, and published in spring of 2015. It took three years.

SEJournal: What was it like to work with a university press?

Jackson: Yale University Press was very nice. They made the book very beautiful. They used some archival photos. I did most of the modern photography of the book. It has black-and-white photos scattered throughout the text and eight pages of color plates. The editor was really nice, the art staff was good to work with. I have nothing but wonderful things to say.

SEJournal: What have you done to sell it? How are sales going?

We are finding out something …

that the puffin is

a canary of climate change.

Jackson: It never threatened to be a NY Times best seller, but Steve is an international ambassador for the birds and I get calls for many solo talks as co-author. There’s a lot of common interest in conservation in the bird world. We are finding out something Steve never anticipated, that the puffin is a canary of climate change.

Waters in the Gulf of Maine are among the fastest-warming large bodies of water on Planet Earth. Because of that, the kinds of fish puffins catch and feed to their chicks are now the most volatile in the history of the project. 2012 was the warmest water in Gulf of Maine in history. As a result, puffins bring in fish known in mid-Atlantic waters. Some are not a problem, but one problematic fish is too oval for chicks to eat. Chicks need thin fish, the fry of herring, haddock, hake, in very young form, that are pencil-like. Chicks can get those down like spaghetti. The fish they are bringing in [butterfish] are too oval for small chicks. Parents bring back fish, but the chicks die of starvation. It’s a volatile population up and down.

Last year the water was fine, and the puffins set a record 172 breeding pairs. Then this summer, the record was broken again, at 178 pairs. It’s great to celebrate, but the larger overall picture is of concern. Globally, in the last five years, puffins have gone from being listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List, to Vulnerable. Warm waters in Europe are affecting southern populations of puffins in Europe. Some populations are crashing. In one place, only 15 percent of chicks survived, but others did well.

Those are real reminders that humans are responsible to maintain the best conditions that still exist for the birds to thrive. In fact, this year, despite the new record of adult breeding puffins on Egg Rock, there were unprecedented shifts in food supply, leading to a disturbing number of underweight chicks.

Derrick Jackson is a 1984 Harvard University Nieman fellow, holds three honorary degrees and a human rights award from colleges in Massachusetts. He is also winner of awards from the National Association of Black Journalists, the National Society of Newspaper Columnists, the National Education Writers Association, the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association, and Columbia University. Jackson also served on SEJ’s board of directors earlier this year.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 3, No. 36. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement