SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

BookShelf: Weather Nerd ‘Looks Up’ and Finds Science, Meaning in Stormy Skies

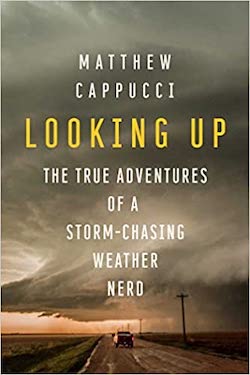

“Looking Up: The True Adventures of a Storm-Chasing Weather Nerd”

By Matthew Cappucci

Pegasus Books, $27.95

Reviewed by Jennifer Weeks

If you watch a lot of weather coverage, you may well have seen Matthew Cappucci’s reports.

|

Cappucci, 24, a meteorologist for The Washington Post, reports for the Fox affiliate in Washington, D.C., and makes videos for the MyRadar weather app. He also makes guest appearances with many other U.S. and international news outlets, especially when major storms hit.

“Looking Up” is Cappucci’s account of growing up obsessed with weather, designing his own major in atmospheric science at Harvard and breaking into major media weather coverage. The book’s promo copy compares him to “Doogie Howser meets Bill Paxton from the movie, Twister, with a dash of ‘Catch Me If You Can,’” but he also evokes comparisons to the Energizer Bunny.

There’s something compelling about people who seem to know what they were born to do from day one, and this book is straight out of that mold. One nice aspect is that Cappucci never pretends his seemingly rapid success was inevitable. He describes rejections, imposter syndrome at Harvard and beyond, storm chases that led nowhere and lonely nights in cheap hotels, where the main solace is alarming quantities of junk food.

There also are really good explanations of many weather and atmospheric science phenomena, from tornadoes to the aurora borealis, or Northern Lights. Cappucci loves to explain the science that creates weather, and journalists who cover storms will find plenty of useful metaphors.

Here is part of his description of supercells, the powerful rotating thunderstorms that produce tornadoes:

Supercells aren’t like ordinary thunderstorms, which clump together into clusters or gusty squall lines. Supercells are small and potent. A single storm may be only five or ten miles wide, but in that tiny space could be packed destructive straight-line winds, softball-sized hail, flooding rains, and tornadoes.

What makes a supercell special is its isolation. While other thunderstorms may compete with neighboring storm cells for resources, supercells exist on their own. That gives them full reign of the surrounding environment — an untapped stockpile of fuel.

And his explanation of a meteor shower:

Meteor showers occur when the Earth passes through a stream of debris left behind by a comet, asteroid or other celestial body during our annual orbit about the sun. (That’s why meteor showers, like the August Perseids or the December Geminids, happen at the same times every year.) The interstellar pebbles, often only the size of a grain of puffed rice, burn up in Earth’s outer atmosphere, combusting as they encounter air while moving at speeds of forty miles or more per second. Imagine driving through a swarm of bugs; when you hit one, it leaves a smear across your windshield.

The sections of the book that connect the weather discussions are a bit more ragged. There’s a lot of jumping around from place to place, and the overall feel is a bit breathless. And when Cappucci ranges beyond meteorology into describing his travels, he has a tendency to throw ten-dollar words around when something simpler would do.

For example, he wrote this about crossing a street in Hanoi: “I silently prayed the traffic would bifurcate around me.” Reflecting on a meteor shower in the desert, he states, “I know my time here is fugacious; that’s why we have to make it count.”

A more assertive editor could have pruned some of these clunkers, and also cleaned up occasional typos (come on, Simon & Schuster!).

Traveling with Cappucci is fun,

even if going in person requires

helmets and safety glasses.

But traveling with Cappucci is fun, even if going in person requires helmets and safety glasses. It’s fun to hear a Gen Zer describe how he anticipated a series of tornadoes that models didn’t project and observe, “When you do this job long enough, you acquire a gut instinct.”

He’s obviously motivated to serve and inform the public. Early in the book, Cappucci wrote about the time he cut high school to fly to Florida, hoping to stand in the eye of his namesake event, Hurricane Matthew. He ended up spending three days in a shelter in Daytona Beach with 154 other people after all the local hotels shut down.

“I witnessed firsthand why many families with children choose not to evacuate, and came to appreciate how many people simply can’t, especially those who don’t have the financial means or who face medical challenges,” he wrote. “My time in Volusia County would make me a better scientist by making me a better human being.”

Jennifer Weeks is senior environment and energy editor at The Conversation U.S. and a former SEJ board member.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 7, No. 45. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement