SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

SEJ News: Author Lopez Remembered; SEJ Speech Reshared

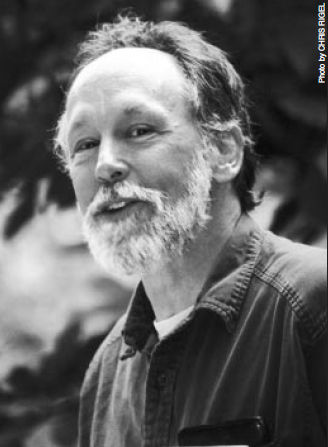

Society of Environmental Journalists' members lamented the Dec. 25 death of renowned nature writer Barry Lopez, whose writings included "Arctic Dreams," "Of Wolves and Men" and other books and magazine articles.

- Barry's website, including "Crossing the River," written by his wife Debra

- "Barry Lopez, Author Who Tied People to Place, Dies at 75," Washington Post, December 27, 2020

- "Barry Lopez, Lyrical Writer Who Was Likened to Thoreau, Dies at 75," New York Times, December 26, 2020, by Robert McFadden

Lopez gave SEJers a much-remembered address about writing, environmental journalism and more at the Barbra Streisand ranch in Malibu during the organization's 1999 annual conference in Los Angeles.

SEJ Conference Director Jay Letto called the talk one of his "top two SEJ talks of all time," along with that of Wendell Berry in Roanoke in 2008. "Both of them nailed the essence and importance of environmental reporting, as well as the emotional toll this particular reporting can take on the reporter," recalled Letto, adding, "This is a huge loss for us."

Lopez's address was later excerpted in the Winter 2000 edition of the SEJournal and is republished below:

Hope amid battle stories: Lopez urges journalists to support each other in undeclared war

|

| Photo courtesy of Chris Rigel |

Excerpted from Barry Lopez's address to SEJ's national conference, Sept. 19, 1999 at the Streisand Center for Conservancy Studies.

By BARRY LOPEZ

So often when you write a story about one or another environmental disaster, you're searching unconsciously for hope.

What is the sentence at the end that will allow the reader to hope, or to believe that it's not all catastrophe and going to collapse like a house of cards on us? The thing that we hold out too often is technology. There is no hope in technology. None. And if you don't believe that, read in the history of science; read in the history of the development of machinery: a new machine brings with it the same old problems. We can manipulate genes and splice things together and create something that will eat oil, so oil spills are okay. Well, what is it that's going to eat up despair? The only way that we are going to get out from underneath this cloak of blight that surrounds us is by changing our behavior, which means fundamentally changing the organization of American culture.

Why is it that we know this and we're not allowed to say it? Because in the reporting of war — which this is — there is always someone in control of the information and someone else who has no say-so or influence or authority. We're stuck in the position of reporting on people — and sometimes working for people — who don't want the war declared, who believe landscapes and people without representation are fodder for an economic system that is destroying civilization. This, of course, is not news. The rapaciousness and the savageness of capitalism is not news.

The question is, what are we going to do in the middle of it as writers, so we don't go crazy? We can bail out and say I've had it with the hypocrisy and the power structure that does not want me to report the story that I found.

I remember — a great piece of education — Harrison Salisbury. Many of you might even have known him and certainly read him when he was writing for The New York Times. Harrison was just too conscientious as a Times reporter. They wanted to restrain him, keep him from turning "minor" stories into major stories, like the politics of communism in China. So they asked him to report on the sanitation industry in New York City.

Harrison put on a pair of coveralls, started riding around on the back of Department of Sanitation trucks, and wrote this multipart series about Mafia influence and corruption in the Department of Sanitation, and the editor said, "What is it with this guy? He can't just go write a simple story; he's got to really write a story."

Ten years ago, floating down the Yangtze River, standing in the bow of the ship with Harrison, I said: "What did you think of the press corps in Beijing?" And he said, "No out-of-town experience."

As many of you know, so often that's the way things work on a foreign desk: here's John in Beijing, and he comes back to the foreign desk and a new guy goes in and has John's Rolodex, and starts calling John's contacts, and then starts making contacts of his own. What he finds out — not news — is that the story John was reporting was a story, but not the story.

Because John is on the foreign desk editing the new guy's copy, if he reports the story John reported it goes right into the paper. But if he writes a story based on his own interpretation or his own investigative reporting, because he's gotten away from the hotel where all the reporters stay, from Reuters and the rest of it, if he got out of town and learned something else, and turned that in, it sat at the edge of the desk for three or four days and then died because that's not the story that we report.

Wait a minute! Why the hell do we have somebody in Beijing to begin with if we already know what the story is?

The darkest element in this — Harrison's great line — is during the height of the Viet Nam war, a couple of writers in New York realized that to go to Viet Nam and write about the war, all you had to do was go to the movies or watch television, because that's what the editors were looking for. So the deal was to stiff a magazine for expenses to go to Viet Nam, and never go, but write a story about which the editor would say, "Holy Christmas, did you get this right!"

You know how difficult this territory is. I am not an optimistic person, given what I have seen. But I will tell you I have every cause to feel hopeful. And the reason for it is that in every dark corner of the world there are men and women who will not go down. They are highly imaginative people, reimagining the circumstances we find ourselves in.

So, at the end here, I want to say that there is hope. And the hope is this: find a way through your profession to aid and abet every human effort to re-establish the authority of community over the notion of the power or rights of the individual. I do not think that there is an individual genius, but I will guarantee you that what passes for genius in human culture is resident in human communities. It may be made manifest in a Beethoven or in a Bach, or in a Melville. But it is not singular; it's not there only in those people. It's our genius that forms the fourth movement of the Beethoven Ninth. So everything that you can do in your own home, and in your professional relationships, and in your work on the street as a reporter, look for, aid and abet community that defies the notion that we're all here in the end just to consume.

Look to stories that show you the power of the human imagination so you know that this isn't something somebody made up, but that in all of these countries, ours included, there are men and women leading extraordinary, un-reported lives, and they are hopeful about our condition because they stayed in touch with all of human history, from the Magdalenian phase of Cro-Magnon culture to today, and they see the testament of what we know, and they aren't giving up.

The last thing I would say about this is take care of each other. Take care of each other. Everybody here has been alone in a news room wondering if it was worth it, or sitting in front of a computer with a deadline at a magazine wondering, "Why am I doing this?" Call each other. Get on the phone with each other. When you see somebody else's story, send them a post card. Let each other know that you're not alone in this. There is a name for what you do, you know, it's part of the title of your professional organization, but that's not who you are. That is not who you are. You're a group of men and women with a skill with language and a desire, in some way, to see the human condition bettered. That's what you are first. You need to call each other and say, "How are you? I missed you. Wasn't it great that we got together in California? You know who we should call? Have you ever thought about... What happened to so-and-so? Is he lost to us?" That's a community. That's where I want to end: Take care of each other.

And thank you for this invitation to come and join you as a colleague.

Barry Lopez has written seven books of fiction and six books of nonfiction, including "Arctic Dreams," winner of the National Book Award; "Of Wolves and Men," winner of the John Burroughs Medal; and "About This Life: Journeys on the Threshold of Memory," a collection of essays that range from the Galapagos to Antarctica. He also writes regularly for magazines including Harper's, where he is a contributing editor.

Advertisement

Advertisement