SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

|

|

A full-grown gray wolf observes biologists in Yellowstone National Park after being captured and fitted with a radio collar. Photo by William Campbell, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. |

Cover Feature

By LAURA LUNDQUIST

The University of Colorado students who showed up for the Biology Club meeting on a winter’s afternoon in 1996 were in for a rare treat.

A discussion of wolves was on the agenda because the long-endangered species was just being reintroduced into Yellowstone National Park and central Idaho. They existed nowhere else in the Western U.S., outside of a few packs in northwestern Montana. So, few students, including me, expected a real wolf to trot into the small classroom and jump on the front table.

I was captivated as Kent Weber of Mission: Wolf, an educational nonprofit based in Westcliffe, Colo., explained wolf behavior while he confined the canine to the tabletop. He said we could look into the wolf’s eyes but not to stare because that was a sign of aggression.

As Weber talked, the wolf’s golden eyes scanned the room and momentarily locked with mine before casually looking away. It was a connection I’ve never forgotten, but even then, there were plenty of people who wouldn’t hesitate to put a bullet between those eyes. Now, 17 years later, wolves have spread through the northern Rocky Mountains, spilling over into adjacent states, and one even made it to California. Others track prey in Michigan, Minnesota and Alaska.

In late April, it was reported that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service was preparing to remove the gray wolf from the endangered species list in the lower 48 states.

Some — namely scientists and wildlife advocates — claim the move is premature, while some wildlife agencies, ranchers and hunters complain it’s long overdue.

For example, at a June 6 Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks meeting, a citizen advisor told the agency director that residents in his county wanted the state to allow more predator control. “Ranchers want to see more done, due to zero tolerance for wolves,” the man said.

Delisting spotlights how conflict, courts define wolf recovery

On June 7, Fish and Wildlife Service Director Dan Ashe for- mally announced the decision to delist the gray wolf (but not the Mexican wolf in the Southwest). A 90-day comment period follows and the final rule will be issued within a year.

Fish and Wildlife’s Ashe justified the delisting, saying that wolf populations were likely to continue growing in range and number beyond the 6,100 now in the U.S.

“Our analysis suggests that the gray wolf no longer faces the threat of extinction or requires the protection of the Endangered Species Act,” Ashe said. “Wolves cannot physically occupy all of their historic range but they don’t need that to be recovered.” In Montana, wolf-hunt changes alone can prompt around 30,000 e-mails, both pro and con, so the Fish and Wildlife office will no doubt be buried in comments.

Such polarization, along with political interference and legal challenges, has driven the trajectory of wolf recovery, which in turn influenced the evolution of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (for more on the Endangered Species Act, see our separate feature on the opposite page). The ESA was modified through the years to try to ensure incremental wolf successes, but some tweaks may have hampered the final outcome.

Some say delisting and hunts are signs of the wolf’s success. The Rocky Mountain population alone has grown to almost 1,700 from the original 66 transplanted in 1995.

But beyond the numbers, there was a hope that once wolves be- came more common, the initial fervor would die down. That hasn’t happened yet.

Communities that seem to have settled down can explode into pent-up rage over livestock deaths or debates over hunting regulations.

“A lot of this was done without thinking ahead; it was basically wishful thinking,” said Brooks Fahy of the Eugene, Ore.-based Predator Defense. “Meanwhile this anti-wolf thing developed. There’s no way you can say this has been a success – it’s a failure with tens of millions of dollars wasted.”

When lawmakers crafted the ESA, they needed to give the law some teeth.

In a move that would probably be avoided today, they chose to give special emphasis to citizen suits. They depended on the public to keep agencies honest while science was supposed to drive the process.

In recent years, that’s been turned on its head.

Citizen suits have initiated almost all Fish and Wildlife Service actions, according to the Center for Biological Diversity, headquartered in Tucson. Science has been pushed to the backseat.

That litigious trend could continue past delisting.

“Our position has always been that wolves should have full protection until they’re recovered. When they delist, we’ll sue on that,” said Mike Garrity, executive director of Alliance for the Wild Rockies in Helena, Mont. Garrity’s group was behind several of the big suits that pushed wolves back onto the list every time Fish and Wildlife tried to remove protections.

But they weren’t the only plaintiffs. During the past 17 years, organizations on both sides of the wolf issue have multiplied. By 2009, 14 organizations had joined the lawsuits to keep wolves listed.

|

|

|

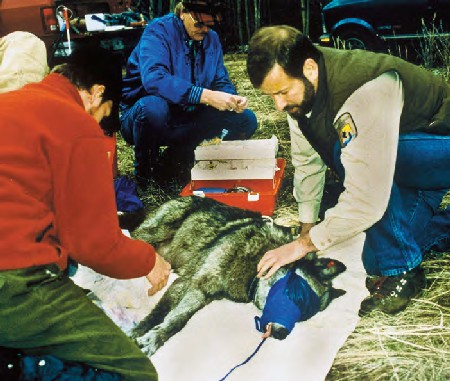

A gray wolf receives a health examination after capture in Canada in 1996. Wolves were later released in the United States in an effort to establish self-sustaining populations, so the species could eventually be removed from the endangered species list. Photo: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. |

ESA “hijacked by politics”

If the courts took the lead role in the first decade of the 21st century, the second decade saw politics reassert itself.

Sen. Jon Tester (D-MT) was just a few years away from a tough re-election in 2012. Montana and Idaho had just held their first wolf hunts in 2009, only to see their authority yanked away by the courts.

Many rural residents were furious over what they saw as an activist court.

Their frustration was often goaded by stories – true or not – of ranchers who couldn’t continue to operate in wolf country or misguided percep- tions that big game herds were being decimated by wolf packs alone.

Even now, when the press reports any negative trend in elk numbers, comment pages fill with barstool biologists indicting wolves.

So, like many Western legislators, Tester cosponsored a bill in September 2010 to take wolves in Montana and Idaho off the endangered species list. By March 2011, most of the 14 environmental groups settled their delisting challenges.

“The 10 big groups decided to settle because they worried it would hurt Tester’s re-election,” Garrity said.

Mike Leahy of Defenders of Wildlife, based in Washington, D.C., told Northwest News Network that he settled because law- suits were becoming increasingly controversial. Environmentalists often won cases on technicalities, but were losing in the court of public opinion, Leahy said.

Yet just as hunters and ranchers were angered when courts took their say away, Garrick Dutcher of Living With Wolves in Sun Valley, Idaho, was infuriated that politics muted his say.

“The Endangered Species Act was hijacked by politics. These are decisions that should be made by scientists,” Dutcher said.

Wolf’s story a challenging one for reporters

For environmental journalists covering the wolf, the decades of twists and turns make the story of wolf recovery difficult to tell. The many details and nuances rarely fit neatly into a 500-word news story or even a 1,500-word feature.

Simplification and labeling of players can lead to inaccuracies.The cast of characters populates a spectrum running from those who would kill every wolf to those who want to save every one. Those at the extremes tend to be the loudest and are not prone to compromise, giving each group its bad rap.

Yet not all ranchers and hunters hate wolves, and not all wolf advocates oppose hunting wolves. While Predator Defense wants no wolves killed, the Montana Wildlife Federation supports wolf hunting as a way to gain acceptance for wolves.

“It’s unrealistic to think we would never have hunting. Some wolves will have to die so others can live,” said Montana Wildlife Federation spokesman Nick Gevock.

With news of the June 7 delisting, it was the no-kill groups that jumped to rally their supporters, claiming that wolves hadn’t been restored to their historic habitats and that delisting would allow wolves to be increasingly shot and trapped.

A primary reason the no-kill groups oppose delisting is they say they distrust state management.

While Oregon has a fairly progressive wolf-management plan — modified at the end of May to make killing a last resort for wolves that prey on livestock — states like Wyoming wanted to treat wolves as “varmints” with unrestricted hunting.

“Wolves would have never recovered under state management,” Dutcher said. “Every state is trying to figure out how to kill wolves, lobbied by agriculture and hunters.”

Fish and Wildlife Service managers set the minimum population for recovery at 300 wolves and 10 breeding pairs in Montana, Idaho and Wyoming.

Many state politicians, urged on by their rural constituents, have tried to enact legislation to knock populations back down to the minimum. In Idaho, a rancher tried to pass a bill that would have allowed aerial shooting and the use of live bait to lure wolves to traps or riflemen.

Thus the wolf is the only recovered species where the population is not encouraged to increase.

“From the get-go, it was anticipated that states would take over recovery but not to just keep it on life support,” said Defenders of Wildlife conservationist Suzanne Stone. “You can’t maintain low numbers and still call it recovery.”

As the states take over and hunting is established nationwide, time will tell whether the wolf’s first 17 years of successful reintroduction continues.

Laura Lundquist is the environmental and political reporter for the Bozeman Chronicle in Bozeman, Mont. She has worked for other newspapers in Montana and Idaho. She received her master’s degree in journalism from the University of Montana in 2010 after working in the fields of environmental consulting and aviation. Follow her on Twitter at @llundquist.

* From the quarterly newsletter SEJournal, Summer 2013. Each new issue of SEJournal is available to members and subscribers only; find subscription information here or learn how to join SEJ. Past issues are archived for the public here.

Advertisement

Advertisement