SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

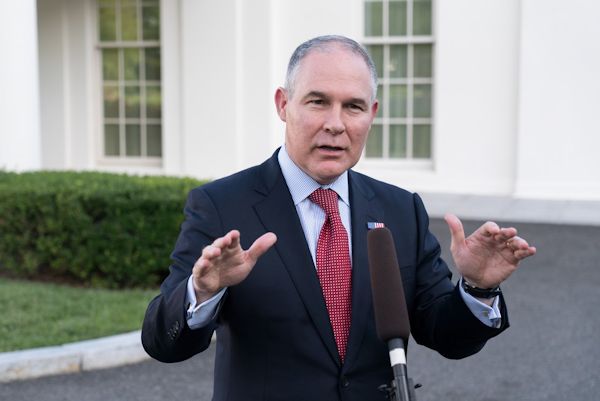

| EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt at a White House-organized “regional media day” on July 25, 2017, which the Associated Press reported favored conservative media outlets. Photo: White House/Mitchell Resnick |

WatchDog: Sun Doesn’t Shine at Trump Environmental Agencies

By Joseph A. Davis, WatchDog TipSheet Editor

Sunshine Week is coming up March 11-17. Organized by the American Society of News Editors and the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, it’s meant to be an annual celebration of access to public information.

But for reporters covering the Scott Pruitt U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, there’s not much to celebrate. This month’s WatchDog catalogues some of the troubling trends at the all-important EPA, as well as other agencies in the Trump administration.

1. Secrecy over travel, meetings at EPA, Interior

2. EPA Press Policy: Watchdogs, Lapdogs and Attack Dogs

3. Institutional Secrecy and Silencing Employees at EPA

4. Deleting the (Climate) Science

1. Secrecy over travel, meetings at EPA, Interior

Reporting on environmental agencies in the Trump administration poses many challenges to journalists faced with secrecy, hostility and misdirection.

On his 2016 campaign, President Donald Trump vowed to mostly eliminate the EPA. As he has dismantled environmental protections piece by piece, the U.S. public’s view of the damage has been obscured by a set of policies that makes EPA and other agencies harder to see and hold accountable.

Emily Holden at Politico reported Feb. 26 that Freedom of Information Act lawsuits against EPA were surging as the agency kept officials’ schedules, meetings and policy decisions secret. One kind of information at issue is details of EPA Administrator Pruitt’s meetings with lobbyists and CEOs of companies his agency regulates.

Some of those trying to get the information have been journalists — although environmental groups and open-government groups have also been in the mix.

Politico counted 55 recent public records lawsuits against the EPA, using data compiled by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. A related study by the Project on Government Oversight, a nonprofit citizens’ group, found that the EPA administrator’s office had significantly delayed the processing of FOIA requests.

First class for Pruitt?

Some of those requests were for Pruitt’s travel records — which became a point of scandal after it was revealed that he was flying first class at taxpayer expense. Rules require each instance of first-class travel to be justified individually.

“The transparency of travel records is more than

a matter of nosy reporters seeking ‘gotcha’ news.

In Pruitt’s case, it raises issues of public accountability.”

An EPA press spokesperson told reporters that Pruitt had a “blanket waiver.” But the spokesperson’s statement turned out to be untrue. The security concerns cited by EPA for the luxury seating turned out to be members of the public complaining in vulgar language that he was ruining the environment. Now the GOP-led House Oversight Committee is seeking Pruitt’s travel records too.

Press accounts of extravagant travel have already led to resignation of one Trump cabinet member. But the transparency of travel records is more than a matter of nosy reporters seeking “gotcha” news. In Pruitt’s case, it raises issues of public accountability — and whether he is avoiding the public whose health he is supposed to be protecting. But it also lays bare his priorities and idea of what his mission is.

Why, some have asked, did Pruitt feel a need to travel to Morocco for four days in December 2017 to promote fossil fuel use? Other questions were raised about a Pruitt trip to Rome in June 2017.

Earlier, documents obtained by the Environmental Integrity Project showed that Pruitt had spent 42 out of 93 days between March and May 2017 either in his home state of Oklahoma or travelling to or from the state.

Most recently, the intense news media scrutiny of his travel seems to have caused Pruitt to postpone a planned trip to Israel. How that trip would relate to EPA’s mission is still an unanswered question.

Investigation into Zinke travel

Different questions and controversies have arisen around the travel of Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke. These have been covered extensively by various news media.

|

| Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke (second from left) receives an inflight briefing on wildland fires in the Pacific Northwest and Northern Rockies before arriving in Montana, on August 24, 2017. Photo: USDA/Lance Cheung |

For example, journalists and critics have asked whether taxpayer funds are being used to pay for Zinke’s political appearances and fundraising, whether funds for fighting wildfire have been diverted for Zinke’s personal travel, and whether unusually expensive modes of travel were used just for his personal convenience.

Interior’s inspector general has opened an investigation into some of these issues.

One telling twist to the story: Interior’s IG said in November that its investigation had encountered obstacles because Zinke’s office had not properly and completely documented (may require subscription) the travel.

That only underlined the critical importance of transparency of government records. Not just journalists, but lawful government investigators — and the public whose interests they represent — need access to documents to hold officials accountable for their actions.

Previous administrations have been more open with records than the Trump administration. During the Obama EPA administration, for example, top officials’ schedules and travel records were made public without a need for FOIA requests. Obama White House visitor logs were made public, while the Trump White House does not willingly disclose them.

Concerns over ‘regulatory capture’

Why should it matter who meets whom — and whether the public knows about it? Corruption is one reason. Or, to put it in more wonkish terms, “regulatory capture.”

Regulatory agencies like EPA are governed by the Administrative Procedure Act — which requires that regulated industries communicate with regulating agencies on the record in ways that the public and courts can see. Industries influence agencies to rule in their interests (and against the public interest) by many means — including political fundraising. Without meeting records, questionable lobbying efforts can take place entirely out of public view.

This is not a theoretical or academic concern. Pruitt, before his appointment to EPA, worked tirelessly and prodigiously in court to oppose EPA’s environmentally protective policies. Through the Republican Attorneys General Association, he raised money from regulated industry groups and launched multiple lawsuits against EPA. Moreover, he worked very hard to keep the public from knowing about the money connection.

Only dogged reporting by the likes of Eric Lipton and Nick Surgey — along with persistent FOIA lawsuits — brought the details into public light. The Trump administration, a year of reporting has confirmed, is deeply indebted to the coal, oil and gas industries, and is hard at work destroying EPA rules (like the Clean Power Plan) that they oppose.

A concrete example of such anti-environmental action at EPA is the chlorpyrifos decision announced in March 2017. Chlorpyrifos is a pesticide used on food crops. EPA scientists had found that chlorpyrifos in sufficient amounts could cause brain damage to kids, and EPA had been set under Obama to declare zero tolerance for chlorpyrifos residue in food, effectively banning it.

Most chlorpyrifos is made by Dow Chemical, which had been a strong Trump supporter. Dow gave $1 million to the Trump inaugural. Dow also asked EPA to set aside its planned science-based ban on chlorpyrifos. And EPA, on March 29, 2017, ignored the evidence (may require subscription) and did just that.

Now, about the meeting records. Associated Press reporter Michael Biesecker sought Pruitt’s calendar to determine whether Pruitt had met with Dow CEO Andrew Liveris before setting aside the chlorpyrifos ban. EPA would not supply Pruitt’s calendar, so Biesecker FOIA’d it and got it. The calendar showed a half-hour meeting between Pruitt and Liveris on March 9, which was reflected in the original AP story.

EPA later complained that the meeting it had documented had not been more than a quick handshake, and AP corrected its story. EPA’s press office made a big deal about this, using the incident to attack Biesecker.

EPA’s attack, however, was a diversion. Liveris had been invited to the ceremony where Trump himself signed an executive order on deregulation. Trump gave Liveris the pen.

The records that have been released show, time and again, Pruitt meeting with industry groups (may require subscription) just before he deregulates them.

2. EPA Press Policy: Watchdogs, Lapdogs and Attack Dogs

If you read the WatchDog, you may be aware that the EPA press office’s relations with the news media have not been sweet and smooth in recent memory. But under EPA Administrator Pruitt it is worse.

One hallmark of the Trump administration is to attack the press at every turn for reporting on Trump’s failings. Trump calls Pulitzer winners “fake news” and the media “the enemy of the American people” (may require subscription). What we began seeing in 2017 was the “Trumpification” of the EPA press office. The basic policy: When agency actions are criticized, attack the press.

The WatchDog has chronicled some of this shift in previous issues, and the Society of Environmental Journalists, as an organization, has complained to EPA about it.

An example was an Associated Press story published Sept. 3, 2017, in the immediate wake of Hurricane Harvey. The story noted flooding at some Houston-area Superfund hazardous waste cleanup sites, and asked whether the waters were spreading contamination.

The EPA press office’s response was to attack the main reporter personally, and falsely claim that the AP had not visited the sites. (AP accompanied its story with onsite video.) In fact, it was EPA that had been AWOL during the emergency, and the attacks on the AP seemed an effort to distract the public from this.

A subsequent story by the New York Times documented (may require subscription) how flooded Superfund sites could be a serious problem in many parts of the United States.

Intimidation tactics against reporters

The example was not unique. The EPA press office has attacked many of the other renowned and accomplished reporters who have been digging up the secrets that the Pruitt administration would rather the public remained ignorant of.

They made a similar attack on the New York Times' Eric Lipton for reporting that Pruitt had reversed the imminent Obama ban on chlorpyrifos. They also attacked Lipton for another story he did on Nancy Beck, a chemical industry insider installed by the Trump-Pruitt administration, who had been seeking to weaken EPA rules on how to determine the toxicity of chemicals in commerce (may require subscription). EPA was writing those rules to implement an amended Toxic Substances Control Act, which Congress passed in 2016.

Top Pruitt EPA spokesperson Liz Bowman, herself a chemical industry PR vet, dismissed Lipton’s work as “elitist clickbait.” She did not mention Lipton’s Pulitzer Prize.

“What we began seeing in 2017 was

the ‘Trumpification’ of the EPA press office.

The basic policy: When agency actions

are criticized, attack the press.”

Tough investigative reporters, and the news outlets they work for, are unlikely to be deterred or intimidated by such tactics. But the beat reporters who slog daily through the agency’s regulatory and science news want the simple basics: phone calls returned before deadline, press officers informed about their subjects, interviews with scientists and officials, and answers to simple questions. SEJ members often complain about not getting these things.

Those who monitor Pruitt’s media behavior, however, note a pattern where he shies away from interviews with established news media that have long had credibility and authority (e.g., the “failing New York Times”) and skews toward right-wing, pro-Trump outlets unlikely to challenge him (e.g., Fox). Scott Waldman wrote about this in May 2017 for ClimateWire.

Even getting an accurate and complete accounting of Pruitt’s media appearances is difficult. Lisa Hymas of Media Matters wrote about the rightward slant of Pruitt’s outlets, but added that Pruitt’s official schedule omitted mention of some of Pruitt’s right-wing media appearances. Meanwhile, regular media have gotten used to publishing statements that EPA declined comment or did not respond.

The attack-first approach to media relations was typified by a story first broken in December by a team from Mother Jones — on an EPA press office contract with Definers Corp. “Using taxpayer dollars,” Mother Jones said, “the Environmental Protection Agency has hired a cutting-edge Republican PR firm that specializes in digging up opposition research to help Pruitt’s office track and shape press coverage of the agency.” The firm offered clients “war room” technology for press relations.

After brisk coverage, EPA abandoned that contract.

The question remains, however, as to whether that kind of media relations is really good PR. It seems, quite often, to backfire. Is it aimed at an audience of one (Trump), or his base (a minority of voters) or the U.S. public at large? Dan Vergano of BuzzFeed offered an answer in his year-end summary story: “The EPA’s News Office Turned Itself Into A Bad News Story In 2017.”

3. Institutional Secrecy and Silencing Employees at EPA

Secrecy at the Pruitt EPA is not just for the news media. It’s an institutional policy, what Thomas Carper, the ranking Democrat on the Senate Environment Committee, calls a “culture of secrecy” — focused especially around Pruitt himself.

The biggest threat that seems to worry Pruitt is that somebody might find out what he is up to.

The New York Times’ Coral Davenport and Eric Lipton wrote about this (may require subscription) in August 2017. Pruitt protects himself from EPA’s own employees. They sometimes are not allowed to take notes at meetings with Pruitt, and must give up their cell phones. Doors to Pruitt’s floor of the building are often locked, and EPA employees must often have an escort to access his floor. Even at EPA headquarters, armed guards shadow him.

“Keeping EPA employees quiet and

away from reporters, it seems, is part

of the Pruitt administration’s mission.”

Is the secrecy a serious problem? Just in February 2018, two open-government groups filed a lawsuit against EPA and Pruitt, charging that the agency failed to keep records as required by law. The groups are Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility and Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington.

A notorious example is the soundproof phone booth. Brady Dennis of the Washington Post reported in September (may require subscription) 2017 that EPA was spending almost $25,000 on a phone booth for Pruitt’s office engineered to prevent eavesdropping or wire-tapping. EPA already had a secure communications facility on another floor.

At the request of House Democrats, EPA’s inspector general is now investigating (may require subscription) whether the decision to approve the phone booth was legally appropriate.

Keeping EPA employees quiet and away from reporters, it seems, is part of the Pruitt administration’s mission. In September, most EPA employees were required to undergo anti-leak training.

Even more ominous, perhaps, was the disclosure in December that executives of Definers Corp. (the “war room” media relations folks) had spent a good part of 2017 scouring EPA for employees (may require subscription) who might view Pruitt’s policies unfavorably. Not just the media, but EPA employees themselves had become the enemy.

4. Deleting the (Climate) Science

On some levels, the EPA has succeeded in keeping information away from the public.

For instance, in the past year, it has scrubbed a lot of science, especially information about climate change, from its website. According to Reuters, the order to do this came straight from the White House.

One reason we know this is from monitoring by a devoted network of “data rescue” activists who track what gets deleted or changed on EPA web pages. At the center of the effort is the Environmental Data & Governance Initiative. The latest installment of EDGI’s reports came out in January 2018.

There are other accounts of the Pruitt EPA preventing its scientists from attending meetings where they might reveal what they have learned from their research.

The good news, if there is any, is that climate science does not really go away or become discredited even when the Trump-Pruitt administration deletes it.

EDGI leads a collaborative effort to archive EPA climate information, so the public can access it even after the Pruitt EPA deletes it. And a number of U.S. cities, such as Chicago and Portland, have joined the effort by posting the climate information EPA deletes from its site.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 3, No. 10. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement